discourses of autoamputation

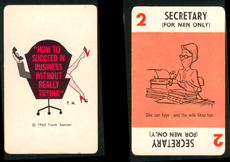

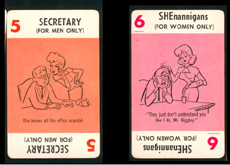

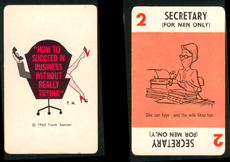

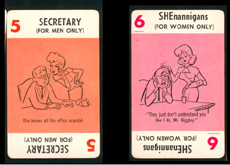

In the 1962 Milton Bradley board game "How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying", the 'Secretary' cards can only be held by male players; 'SHEnannigans' cards are played by women. These secretary jokes and jibes hinge on anxiety about gender trouble. Does the secretary's intermediary position mark both lack and unwillingness to acknowledge lack? McLuhan describes the technologically extended body as 'autoamputated'; technology rewires the body in terms of lack.

"Any invention or technology is an extension or self-amputation of our physical bodies, and such extension also demands new ratios or new equilibriums among the other organs and extensions of the body." ("The Gadget Lover / Narcissus as Narcosis", 41)

Like the electronic sweatshop worker in her over-lit telemarketing cubbyhole, the (auto) neutered couch potato could be read in terms of castration, a fate accepted in exchange for becoming what McLuhan calls the 'sexual organs' of the machine.

"Man becomes, as it were, the sex organs of the machine world, as the bee of the plant world, enabling it to fecundate and to evolve ever new forms. The machine world reciprocates man's love by expediting his wishes and desires, namely, in providing him with wealth." (Ibid. 46)

Techno-jouissance cheats death through techno-reproduction and wealth-breeding. In this narrative, the secretary and the machine world's interface mechanism are linked; both provoke what Sandilands calls erotophobia.

"Erotophobia, it seems, bespeaks a fear of death; the channeling of desire into narrow reproductive acts serves to mark, erroneously, the possibility of immortality in the threatening darkness of death." (181)

Continuing down the Freudian path, we find the pleasures of technology are perilous. Grosz describes the terrain in her discussion of Caillois and

"the mechanisms of automatism, and the female android By making sex something to die for, something that is a kind of anticipation of death (the 'little death'), woman is thereby cast into the category of the non-human, the non-living, or a living threat of death." (Grosz, 194)

Desire cleaves the secretarial typist from the office-femme-fatale, but the boundary between the de-sexed and hypersexed techno-females is porous. Enmeshed in castration discourses, secretaries mutate, like Braidotti's 'inse(x)ts', between non-reproductive droids and man-eaters.

"Women possess as part of their genitals a small organ similar to the male one." (Freud, Introductory Lectures on Pyscho-Analysis, 1915-1916)

The 'masculinity complex' is rooted in the little girl's certainty that her 'tiny' clitoris will grow into a (big) penis, to be exchanged for a (fantasy) phallus. This motif is counter-productive when theorizing miniaturization, the trend toward tinier interfaces yielding larger washes of effect that characterize the electronic desirables discussed here. Electronic miniaturization reverses the dynamics of scale in Freud's description. (As my daughter put it, "penis envy is a stupid idea, because everyone has a penis" - which could be interpreted, 'everyone (lucky) has a (tinier, more concentrated) clitoris')). Perhaps the fingerpads of techno-digitalia have more in common with fetishes?

"A fetish is a metonym related to the penis but in no way resembling it. The fetish is not a replacement penis; rather, it is a 'fantasy-phallus'." (Bersani and Dutoit qtd. in Grosz 164)

calibrating the cyberverse

The 'mountains and molehills' of the Freudian lexicon, so labouriously re-coded in feminist critique, create barriers in re-theorizing the small actions of the hands, the keys to calibrating the cyberverse at the moment. This vocabulary and theory seems ill-fitted with interfaces as they stand. Grosz notes,

"If bodies are to be reconceived, not only must their matter and form be rethought, but so too must be their environment and spatio-temporal location. space and time remain conceivable only insofar as corporeality provides the basis for our perception and representation of them. (Grosz, 84)

Following Grosz's itinerary of investigation, how does our handiwork - my embodied knowledge of the keyboard, and my daughter's of the game controller - configure our spatio-temporal location? . What is the time-space of the exquisitely rapid, delicate play of fingertip on buttons that is the agency of the keyboard, the game-controller?

Donna Haraway's attention to our permeable contact zones with computers troubles dualisms between mind and body :

"It is not clear what is mind and what body in machines that resolve into coding practices. In so far as we know ourselves in both formal discourse (for example, biology) and in daily practice (for example, the homework economy in the integrated circuit), we find ourselves to be cyborgs, hybrids, mosaics, chimeras." (Haraway, 177).

Since Donna Haraway wrote the above in 1991, the body/space of the hands and the keyboard/mouse/controller has become the centrifugal site where we "jack in" to the Internet. One has to dig into Haraway's conjectures to find much about the Internet. Her citations of Winograd and Flores' theories of computing design are pertinent to the Internet's instability, its viruses, cybersilt and junk mail, in terms of breakdown :

"Breakdown plays a central role in human understanding. A breakdown is not a negative situation to be avoided, but a situation of non-obviousness, in which some aspect of the network is brought forth into visibility This creates a clear objective for design - to anticipate the form of breakdowns and provide a space of possibilities for action when they occur." (Winograd qtd. in Haraway 214)

Breakdown (like the non-obviousness one encounters while gaming) is usefully located by Winograd as a site for learning and creative agency.(2.)

"Web spider' and 'web crawler' are names that point to the arachnoid character of web-embodied knowledge, its stickiness, as well as our pattern of maneuvering through it. In a 'Wired' survey (2001), most who were asked, "What is your favourite web site?" chose Google, the web crawler/search engine. 'Googling' in some academic circles is a verb for spurious Internet research. The speed with which internet researchers may initiate dialogue with the authors of texts, or bring texts into unexpected collision - in short, interactivity - is a productive difference from print research.

We are in constant contact with keyboards now and these hold a clear place historically in categories of women's work and workplaces. A keyboard is foregrounded in Haraway's cover illustration of a cyborg/typist, but Haraway does not account much for fingertip fluency (she references William Gibson, but not his attention to this 'hacker' aptitude.) Internetwork draws an embodied dance of the hands on keyboard from domestic spaces into provisional social alignments, with the possibility of facilitating collaboration, mutation and coalition. Perhaps we can circulate within the meanings and histories of 'typewriter writing', ecriture feminine, e-mail exchanges and e-zines, for example, as sites of intersecting productivity.

full-body conjectures

N. Katherine Hayles cites research that suggests women have more difficulty navigating from a virtual pov :

"As a marker of subjectivity, pov is more than an acronym, more even than a noun. In the parlance of VR, it functions like a pronoun, a semiotic container for subjectivity (researchers conjecture) that men adapt more readily to the idea that pov can move independently of the body, whereas women are accustomed to identifying pov with the body." (Hayles, p. 14)

This suggestion is problematic. Attention to fluency in the hand-techniques of gaming and keyboard navigation might trouble this reading of women's bodies. However, Hayles' text conjectures about 'full body' interfaces that would restore the body's wholeness and scale. In this conjecture, the future includes 'smart suits' and immersive electronic architectures that expand the skin/technology interface beyond the hands to a future spatio-temporal location where movement through information will include walking and dancing. This technology - though research is underway - is 'uncertain'. Grosz writes,

"The implosion of space into time, the transmutation of distance into speed, the instantaneousness of communication, the collapsing of the workspace into the home computer system, will clearly have major effects on the bodies of the city's inhabitants Whether this results in the 'crossbreeding' of the body and machine -- whether the machine will take on the characteristics attributed to the human body ("artificial intelligence", automatons) -- or whether the human body will take on the characteristics of the machine (the cyborg, bionics, computer prosthesis) remains unclear." (Grosz, 110)

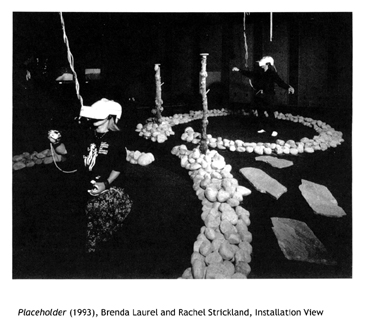

Several feminist art works have prototyped performative body/firmware and immersive spaces, for example, Brenda Laurel and Rachel Strickland's Placeholder (1991) mounted at the Banff Centre. In this project, the body is writ-large as interface, using VR goggles and hot-wired gloves, as well as environmental 'real' obstacles - rocks -which the goggled participants stumbled upon (see Plates). Very expensive to mount, Placeholder often crashed (stressful for the artists), existing briefly in the gallery and moving on to occupy a position in critical writing (N. Katherine Hayles, see above). Related sculpture/installations include environmental interfaces with surveillance cameras, motion detectors and large-scale data projection, rescaling interactivity discourses to institutional proportion.(3.)

Several feminist art works have prototyped performative body/firmware and immersive spaces, for example, Brenda Laurel and Rachel Strickland's Placeholder (1991) mounted at the Banff Centre. In this project, the body is writ-large as interface, using VR goggles and hot-wired gloves, as well as environmental 'real' obstacles - rocks -which the goggled participants stumbled upon (see Plates). Very expensive to mount, Placeholder often crashed (stressful for the artists), existing briefly in the gallery and moving on to occupy a position in critical writing (N. Katherine Hayles, see above). Related sculpture/installations include environmental interfaces with surveillance cameras, motion detectors and large-scale data projection, rescaling interactivity discourses to institutional proportion.(3.)

The place of artists in the R. & D. labs of new technologies (promoted by government/ business partnerships) is a site of contestation. Since the cyberfeminist writing of the early to mid-1990's, other public places for digital technology have proliferated : arcades, gaming parlours, Internet cafés and their hybrids, such as the "Internet café and Laundromat", where cheap Internet access is provided alongside other domestic appliances. These places invite inhabitation and critical subversion, providing some ideas for alternative access strategies.

life support systems

Cyborgs - if by that we mean bionically and computer/prosthetically enhanced bodies - are among us now, and many are elderly. Grosz's 'uncertain future' is almost certainly the future of our own bodies, including the maintenance regimes necessary to keep the elderly Cyborgs functioning (and others whose bodies intersect with prosthetic technology). Like finicky home computers, the feeding pumps, dialysis units and colostomy systems crash and break down, and very little training or support exists for Cyborgs, health care workers or domestic companions who keep them operating. This laptop-scale gear is designed for 'consumers', usually people who are low on the rungs of social power including the infirm, recent immigrants, elderly wives, HIV+ companions and middle-aged daughters (often with jobs and dependent children of their own, the so-called 'sandwich' generation). Where does this daily grind of plugging, unplugging, washing, sterilizing and calibrating life-support mechanisms fit on the cyber-theory continuum? It is difficult to attend to the sites of body/machine interface (prone as these are to blockages, leaky plugs, irritation and infection).The inside-out Cyborg bodies are stigmatized; their exposed fluid processes pose a challenge to the architecture and planning of social space, and provoke confrontation with our culture's ageism and discrimination against physical (dis)ability. (4.)

<< previous page home next page >>